College of William & Mary

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

| |

| Latin: Collegium Gulielmi et Mariae[1] | |

| Type | Royal college (1693–1776) Private college (1776–1906) Public research university |

|---|---|

| Established | February 8, 1693[2][a] |

| Accreditation | SACS |

Religious affiliation | Nonsectarian, formerly Church of England and Episcopal Church |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $1.5 billion (2024)[3] |

| Chancellor | Robert Gates |

| President | Katherine Rowe |

| Rector | Charles Poston |

Academic staff | 738 full-time, 183 part-time (2020)[4] |

| Students | 9,818 (fall 2024)[5] |

| Undergraduates | 7,063 (fall 2024)[5] |

| Postgraduates | 2,755 (fall 2024)[5] |

| Location | , , United States 37°16′15″N 76°42′30″W / 37.27083°N 76.70833°W |

| Campus | Small suburb, 1,200 acres (490 ha) |

| Other campuses | |

| Newspaper | The Flat Hat |

| Colors | Green and gold[6] |

| Nickname | Tribe |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | The Griffin |

| Website | wm |

| |

The College of William & Mary[b] (abbreviated as W&M[8]) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. Founded in 1693 under a royal charter issued by King William III and Queen Mary II, it is the second-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and the ninth-oldest in the English-speaking world.[9] William & Mary is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[10] The university is among the original nine colonial colleges.

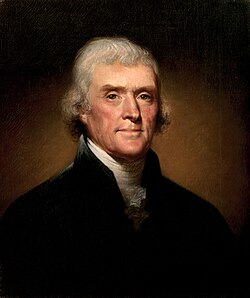

The college educated American Presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and John Tyler. It also educated other key figures pivotal to the development of the United States, including the first President of the Continental Congress Peyton Randolph, the first U.S. Attorney General Edmund Randolph, the fourth U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, Speaker of the House of Representatives Henry Clay, Commanding General of the U.S. Army Winfield Scott, sixteen members of the Continental Congress, and four signers of the Declaration of Independence. Its connections with many Founding Fathers of the United States earned it the nickname "the Alma Mater of the Nation".[11] George Washington received his surveyor's license from the college in 1749, and later became the college's first American chancellor in 1788. That position was long held by the bishops of London and archbishops of Canterbury, though in modern times has been held by U.S. Supreme Court justices, Cabinet secretaries, and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Benjamin Franklin received William & Mary's first honorary degree in 1756.[12]

William & Mary is notable for its many firsts in American higher education. In 1736, W&M became the first school of higher education in the future United States to install a student honor code of conduct.[13] The F.H.C. Society, founded in 1750, was the first collegiate fraternity in the United States, and W&M students founded the Phi Beta Kappa academic honor society in 1776, the first Greek-letter fraternity. It is the only American university issued a coat of arms by the College of Arms in London.[14] The establishment of graduate programs in law and medicine in 1779 makes it one of the first universities in the United States. The William & Mary Law School is the oldest law school in the United States, and the Wren Building, attributed to and named for the famed English architect Sir Christopher Wren, is the oldest academic building still standing in the United States.[15]

History

[edit]Colonial era (1693–1776)

[edit]

A school of higher education for both Native American young men and the sons of the colonists was one of the earliest goals of the leaders of the Colony of Virginia. The college was founded on February 8, 1693, under a royal charter to "make, found and establish a certain Place of Universal Study, a perpetual College of Divinity, Philosophy, Languages, and other good arts and sciences ... to be supported and maintained, in all time coming."[16] Named in honor of the reigning monarchs King William III and Queen Mary II, the college is the second-oldest in the United States. The original plans for the college date back to 1618 at Henrico but were thwarted by the Indian massacre of 1622, a change in government (in 1624, the Virginia Company's charter was revoked by King James I and the Virginia Colony was transferred to royal authority as a crown colony), events related to the English Civil War, and Bacon's Rebellion. In 1695, before the town of Williamsburg existed, construction began on the College Building, now known as the Sir Christopher Wren Building, in what was then called Middle Plantation. It is the oldest college building in America. The college is one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution. The charter named James Blair as the college's first president (a lifetime appointment which he held until he died in 1743). William & Mary was founded as an Anglican institution; students were required to be members of the Church of England, and professors were required to declare adherence to the Thirty-Nine Articles.[17]

In 1693, the college was given a seat in the House of Burgesses, and it was determined tobacco taxes and export duties on furs and animal skins would support the college. The college acquired a 330 acres (1.3 km2) parcel for the new school,[18] 8 miles (13 km) from Jamestown. In 1694, the new school opened in temporary buildings.

Williamsburg was granted a royal charter as a city in 1722 by the Crown and served as the capital of Colonial Virginia from 1699 to 1780. During this time, the college served as a law center, and lawmakers frequently used its buildings. It educated future U.S. Presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and John Tyler. The college has been called "the Alma Mater of a Nation" because of its close ties to America's founding fathers and figures pivotal to the development and expansion of the United States. George Washington, who received his surveyor's license through the college despite never attending, was the college's first American chancellor. William & Mary is famous for its firsts: the first U.S. institution with a royal charter, the first Greek-letter society (Phi Beta Kappa, founded in 1776), the first collegiate society in the country (F.H.C. Society, founded in 1750), the first student honor code and the first collegiate law school in America.[c][19]

Revolution and transition

[edit]During the American Revolution, Virginia established a freedom of religion, notably with the 1786 passage of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. Future U.S. President James Madison was a key figure in the transition to religious freedom in Virginia, and Right Reverend James Madison, his cousin and Thomas Jefferson, who was on the Board of Visitors, helped the College of William & Mary to make the transition as well. In 1779, the college established graduate schools in law and medicine, making it one of the institutions that claimed to be the first university in the United States. As its president, Reverend Madison worked with the new leaders of Virginia, most notably Jefferson, on a reorganization and changes for the college which included the abolition of the Divinity School and the Indian School and the establishment of the first elective system of study and honor system.[20]

The College of William & Mary is home to the nation's first collegiate secret society, the F.H.C. Society, popularly known as the Flat Hat Club, founded on November 11, 1750. On December 5, 1776, students John Heath and William Short (class of 1779) founded Phi Beta Kappa as a secret literary and philosophical society. Other secret societies known to exist at the college currently include: The 7 Society, 13 Club, Alpha Club, Bishop James Madison Society, The Society, The Spades, W Society, and Wren Society.[21][22]

Thomas R. Dew, professor of history, metaphysics, and political economy, and then president of William & Mary from 1836 until he died in 1846, was an influential academic defender of slavery.[23]: 21–47

In 1842, alumni of the college formed the Society of the Alumni[24] which is now the sixth oldest alum organization in the United States. In 1859, a great fire destroyed the College Building. The Alumni House is one of the few original antebellum structures remaining on campus; notable others include the Wren Building, the President's House, the Brafferton, and Prince George House.

Civil War, Reconstruction, and the early 20th century

[edit]

At the outset of the American Civil War (1861–1865), enlistments in the Confederate States Army depleted the student body. On May 10, 1861, the faculty voted to close the college for the duration of the conflict. General Charles A. Whittier reported that "thirty-two out of thirty-five professors and instructors abandoned the college work and joined the army in the field".[25] The College Building was used as a Confederate barracks and later as a hospital, first by Confederate, and later Union forces. The Battle of Williamsburg was fought nearby during the Peninsula Campaign on May 5, 1862, and the city was captured by the Union army the next day. The Brafferton building of the college was used for a time as quarters for the commanding officer of the Union garrison occupying the town. On September 9, 1862, drunken soldiers of the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry set fire to the College Building,[26] purportedly in an attempt to prevent Confederate snipers from using it for cover.[non-primary source needed]

Following the restoration of the Union, Virginia was destitute. The college's 16th president, Benjamin Stoddert Ewell, finally reopened the school in 1869 using his funds, but the college closed again in 1882 due to insufficient funding. In 1888, William & Mary resumed operations under an amended charter when the Commonwealth of Virginia passed an act[27] appropriating $10,000 to support the college as a teacher-training institution. Lyon Gardiner Tyler (son of US President and alumnus John Tyler) became the 17th president of the college following Ewell's retirement. Tyler and his successor J. A. C. Chandler expanded the college. In 1896, Minnie Braithwaite Jenkins was the first woman to attempt to take classes at William & Mary, although her petition was denied.[28] In March 1906, the General Assembly passed an act taking over the college grounds, and it has remained publicly supported ever since. In 1918, it was one of the first universities in Virginia to admit women.[29] Enrollment increased from 104 in 1889 to 1269 students by 1932.

W. A. R. Goodwin, rector at Bruton Parish Church and professor of biblical literature and religious education at the college, pursued benefactors who could support the restoration of Williamsburg. Goodwin considered Williamsburg "as the original training and testing ground" of the United States. Goodwin persuaded John D. Rockefeller Jr. to initiate the restoration of Williamsburg in 1926, leading to the establishment of Colonial Williamsburg.[30] Goodwin had initially only pursued Rockefeller to help fund the construction of Phi Beta Kappa Memorial Hall, but had convinced Rockefeller to participate in a broader restoration effort when he visited William & Mary for the hall's dedication. While the college's administration was less supportive of the restoration efforts than many others in Williamsburg–before the Colonial Williamsburg project, the William & Mary campus was Williamsburg's primary tourist attraction–the college's cooperation was secured.[31] Restoration paid for by Rockefeller's program extended to the college, with the Wren Building restored in 1928–1931, President's House in 1931, and Brafferton in 1931–1932.[32][33]

1930–present

[edit]

In 1930, William & Mary established a branch in Norfolk, Virginia called The Norfolk Division of the College of William & Mary; it eventually became the independent state-supported institution known as Old Dominion University.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt received an honorary degree from the college on October 20, 1934.[34] In 1935, the Sunken Garden was constructed just west of the Wren Building. The sunken design is from a similar landscape feature at Royal Hospital Chelsea in London, designed by Sir Christopher Wren.

In 1945, the editor-in-chief of The Flat Hat, Marilyn Kaemmerle, wrote an editorial, "Lincoln's Job Half-Done..." that supported the end of racial segregation, anti-miscegenation laws and white supremacy; the university administration removed her from the newspaper and nearly expelled her.[35] According to Time magazine, in response, over one-thousand William & Mary students held "a spirited mass meeting protesting infringement of the sacred principles of freedom of the press bequeathed by Alumnus Thomas Jefferson." She was allowed to graduate, but future editors had to discuss "controversial writings" with faculty before printing. The college Board of Visitors apologized to her in the 1980s.[36][37]

The college admitted Hulon Willis into a graduate program in 1951 because the program was unavailable at Virginia State. However, the college did not open all programs to African-American students until around 1970.[39]

In 1960, The Colleges of William & Mary, a short-lived five-campus university system, was founded. It included the College of William & Mary, the Richmond Professional Institute, the Norfolk Division of the College of William & Mary, Christopher Newport College, and Richard Bland College.[40] It was dissolved in 1962, with only Richard Bland College remaining officially associated with the College of William & Mary at the present day.

In 1974, Jay Winston Johns willed Highland, the 535-acre (2.17 km2) historic Albemarle County, Virginia estate of alumnus and U.S. President James Monroe, to the college. The college restored this historic presidential home near Charlottesville and opened it publicly.[41]

Jefferson Hall, a student dormitory, was destroyed by fire on January 20, 1983, without casualties. The building, including the destroyed west wing, was rebuilt and reopened.[42]

On July 25, 2012, Eastern Virginia Medical School (EVMS), in nearby Norfolk, Virginia, made a joint announcement with William & Mary that the two schools were considering merging, with the prospect that EVMS would become the William & Mary School of Medicine.[43][44] Any such merger would have to be confirmed by the two schools and then confirmed by the Virginia General Assembly and Governor. Both universities subsequently agreed upon a pilot relationship, supported by a $200,000 grant in the Virginia budget, to examine this possible union in reality.[45]

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, William & Mary has retained its historic ties to the United Kingdom and that state's royal family. In 1954, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother visited William & Mary as part of her tour of the United States, becoming the first member of the royal family to visit the college. In 1957, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, visited the college to commemorate the 350th anniversary of the landing at Jamestown. Queen Elizabeth gave a speech from the balcony of the Wren Building that drew over 20,000 people, the largest crowd ever seen in the city. In 1981, Charles, Prince of Wales, visited to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Yorktown. In 1988, the United States Congress selected William & Mary to send a delegation to the United Kingdom for the 300th anniversary of the ascension of King William III and Queen Mary II. Prince Charles would return to the college in 1993 for the 300th anniversary of William & Mary. William & Mary sent a delegation to meet with Queen Elizabeth II that same year. Former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher would be made the Chancellor of the College of William & Mary that same year. In 2007, Elizabeth II and Prince Philip would visit the college for a second time to recognize the 400th anniversary of the landing at Jamestown.[46] In 2022, a beacon was lit in front of the Wren Building to celebrate the Platinum Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II.[47]

Campus

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Campus of the College of William & Mary |

|---|

|

The college is on a 1,200-acre (490 ha) campus in Williamsburg, Virginia. In 2011, Travel+Leisure named William & Mary one of the most beautiful college campuses in the United States.[48]

The Sir Christopher Wren Building is the oldest college building in the United States and a National Historic Landmark.[49] The building, colloquially referred to as the "Wren Building", was named upon its renovation in 1931 to honor the English architect Sir Christopher Wren. The basis for the 1930s name is a 1724 history in which mathematics professor Hugh Jones stated the 1699 design was "first modelled by Sir Christopher Wren" and then was adapted "by the Gentlemen there" in Virginia; little is known about how it looked since it burned within a few years of its completion. Today's Wren Building is based on the design of its 1716 replacement. The college's alum association has suggested Wren's connection to the 1931 building is a viable subject of investigation.[50]

Two other buildings around the Wren Building compose an area known as "Ancient" or "Historic Campus":[51] the Brafferton (built within 1723 and originally housing the Indian School, now the President and Provost's offices) and the President's House (built within 1732). In addition to the Ancient Campus, which dates to the 18th century, the college also consists of "Old Campus" and "New Campus".[52] "Old Campus", adjacent to Ancient Campus, surrounds the Sunken Garden.[53]

Adjoining "Old Campus" to the north and west is "New Campus". It was constructed primarily between 1950 and 1980, and it consists of academic buildings and dormitories that, while of the same brick construction as "Old Campus", fit into the vernacular of modern architecture. Beginning with the college's tercentenary in 1993, the college has embarked on a building and renovation program that favors the traditional architectural style of "Old Campus", while incorporating energy-efficient technologies. Several buildings constructed since the 1990s have been LEED certified. Additionally, as the buildings of "New Campus" are renovated after decades of use, several have been remodeled to incorporate more traditional architectural elements to unify the appearance of the entire college campus. "New Campus" is dominated by William and Mary Hall, Earl Gregg Swem Library, and formerly Phi Beta Kappa Memorial Hall. It also includes the offices and classrooms of the Mathematics, Physics, Psychology, Biology, and Chemistry Departments, the majority of freshman dormitories, the fraternity complex, the majority of the college's athletic fields, and the Muscarelle Museum of Art. The newest addition to "New Campus" is Alan B. Miller Hall, the headquarters of the college's Mason School of Business.

The recent wave of construction at William & Mary has resulted in a new building for the School of Education, not far from Kaplan Hall (formerly William and Mary Hall). The offices and classrooms of the Government, Economics, and Classical Language Departments share John E. Boswell Hall (formerly "Morton Hall") on "New Campus". These departments have been piecemeal separated and relocated to buildings recently renovated within the "Old Campus", such as Chancellors' Hall.[54][relevant? – discuss]

The vast majority of William & Mary's 1,200 acres (4.9 km2) consists of woodlands and Lake Matoaka, an artificial lake created by colonists in the early 18th century.[55]

Following the George Floyd protests and associated movements, as well as student and faculty pressure in 2020 and 2021, several buildings, halls, and other entities were renamed. Maury Hall (named for Confederate sailor Matthew Fontaine Maury) on the Virginia Institute of Marine Science campus and Trinkle Hall (named for Governor Elbert Lee Trinkle) of Campus Center were renamed in September 2020 to York River Hall and Unity Hall respectively.[56] In April 2021, three buildings were renamed at following a vote by the Board of Visitors: Morton Hall (named for professor Richard Lee Morton) to John E. Boswell Hall (for LGBT advocate and alum John Boswell), Taliaferro Hall (named for Confederate General William Taliaferro) to Hulon L. Willis Sr. Hall (Hulon Willis Sr. was the first Black student at the college), and Tyler Hall (named for President John Tyler and his son) to its original name of Chancellors' Hall (the hall had been renamed in 1988).[54]

Organization and administration

[edit]

The Board of Visitors is a corporation established by the General Assembly of Virginia to govern and supervise the operation of the College of William & Mary and of Richard Bland College.[57] The corporation is composed of 17 members appointed by the Governor of Virginia, based upon the recommendations made by the Society of the Alumni, to a maximum of two successive four-year terms. The Board elects a Rector, Vice-Rector, and Secretary, and the Board meets four times annually.[57] The Board appoints a president, related administrative officers, and an honorary chancellor, approving degrees, admission policies, departments, and schools and executing the fiduciary duties of supervising the college's property and finances.[58]

The Chancellor of the College of William & Mary is largely ceremonial. Until 1776, the position was held by an English subject, usually the Archbishop of Canterbury or the Bishop of London, who served as the college's advocate to the Crown, while a colonial President oversaw the day-to-day activities of the Williamsburg campus. Following the Revolutionary War, General George Washington was appointed as the first American chancellor; later, United States President John Tyler held the post. The college has recently had several distinguished chancellors: former Chief Justice of the United States Warren E. Burger (1986–1993), former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (1993–2000), former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (2000–2005), and former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor (2005–2012).[59] Former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates, himself an alumnus of the college, succeeded O'Connor in February 2012.[60]

The Board of Visitors delegates to a president the operating responsibility and accountability for the college's administrative, fiscal, and academic performance, as well as representing the college on public occasions such as conferral of degrees.[57] W. Taylor Reveley III, 27th President of the college, served from 2008 to 2018.[61] In February 2018, The Board of Visitors unanimously elected Katherine A. Rowe as Reveley's successor. Rowe is the first female president to serve the college since its founding.[62]

Faculty members are organized into separate faculties of the Faculty of Arts and Science as well as those for the respective schools of Business, Education, Law, and Virginia Institute of Marine Science.[57] Each faculty is presided over by a dean, who reports to the provost, and governs itself through separate by-laws approved by the Board of Visitors. The faculty is also represented by a faculty assembly advising the president and provost.[57]

The Royal Hospital School, an independent boarding school in the United Kingdom, is a sister institution.[63]

Academics

[edit]

The College of William & Mary is a medium-sized, highly residential, public research university.[64] The focal point of the university is its four-year, full-time undergraduate program which constitutes most of the institution's enrollment. The college has a strong undergraduate arts & sciences focus, with many graduate programs in diverse fields ranging from American colonial history to marine science. The university offers multiple academic programs through its center in the District of Columbia: an undergraduate joint degree program in engineering with Columbia University, as well as a liberal arts joint degree program with the University of St Andrews in Scotland.[65]

The graduate programs are dominant in STEM fields and the university has a high level of research activity.[64] For the 2016–17 academic year, 1,591 undergraduate, 652 masters, and 293 doctoral degrees were conferred.[66] William & Mary is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.[67]

William & Mary contains several schools,[68] academic departments, and interdisciplinary research institutes, including:

- Arts and Sciences[69]

- Batten School of Coastal & Marine Sciences at VIMS[69][70]

- Raymond A. Mason School of Business[69]

- William & Mary Law School[69]

- William & Mary School of Computing, Data Sciences & Physics[69]

- William & Mary School of Education[69]

William & Mary offers exchange programs with 15 foreign schools, drawing more than 12% of its undergraduates into these programs. It also receives U.S. State Department grants to expand its foreign exchange programs further.[71]

Admissions and tuition

[edit]| Admissions statistics | |

|---|---|

| Admit rate | 32.7% ( |

| Yield rate | 28.2% ( |

| Test scores middle 50%[i] | |

| SAT Total | 1365–1510 (among 45% of FTFs) |

| ACT Composite | 32–34 (among 17% of FTFs) |

| High school GPA | |

| Average | 4.4 |

| |

William & Mary enrolled 7,063 undergraduate and 2,755 postgraduate students in Fall 2024.[73] In 2018, women made up 57.6% of the undergraduate and 50.7% of the graduate student bodies.[66]

Admission to W&M is considered "most selective" according to U.S. News & World Report.[74] For the undergraduate class entering fall 2024, William & Mary received 17,789 applications and accepted 6,063, or 34.0%. Of accepted applications, 1,614 enrolled, a yield rate of 26.6%. Of all matriculating students, the average high school GPA is 4.4. The interquartile range for total SAT scores was 1400–1530, while the range for ACT scores was 32–34.[75]

Undergraduate tuition for 2024–2025 was $18,709 for Virginia residents and $43,442 for out-of-state students.[76] W&M granted over $20.9 million in need-based scholarships in 2014–2015 to 1,734 undergraduates (27.5% of the undergraduate student body); 37% of the student body received loans, and average student indebtedness was $26,017.[77] Research of William & Mary's student budy published in 2016 and 2017 showed students hailed overwhelmingly from wealthy family backgrounds, even as compared to other elite public institutions.[78][79] The college is need-blind for domestic applicants.[80]

Rankings

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[81] | 55 |

| U.S. News & World Report[82] | 54 (tie) |

| Washington Monthly[83] | 109 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[84] | 79 |

| Global | |

| QS[85] | 901–950 |

| THE[86] | 601–800 |

| U.S. News & World Report[87] | 1049 (tie) |

| USNWR Undergraduate Rankings[88] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Program | Ranking | ||

| Biological Sciences | 159 | ||

| Computer Science | 68 | ||

| History | 27 | ||

| U.S. Colonial History[89] | 1 | ||

| Physics | 71 | ||

| Public Affairs | 94 | ||

| Undergraduate Teaching[90] | 4 (tied) | ||

| USNWR Graduate Rankings[88] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Program | Ranking | ||

| Biological Sciences | 158 | ||

| Business | 45 | ||

| Computer Science | 70 | ||

| Earth Sciences | 83 | ||

| Education | 70 | ||

| History | 26 | ||

| Law | 45 | ||

| Physics | 78 | ||

| Public Affairs | 108 | ||

In the 2025 U.S. News & World Report rankings, W&M ranks as tied for the 23rd-best public university in the United States, tied for 54th-best national university in the U.S., and tied for 1049th-best university in the world.[91][92] U.S. News & World Report also rated William & Mary's undergraduate teaching as 4th best (tied with Princeton University) among 73 national universities and 13th best for Undergraduate Research/Creative Projects in its 2021 rankings.[91] In 2025, Forbes ranked William & Mary #43 among research universities.[93] In 2025, College Raptor ranked William & Mary's median SAT score #2 of public colleges and universities in the United States.[94] William & Mary is ranked 3rd for four year graduation rates among public colleges and universities.[95]

In his 1985 book Public Ivies: A Guide to America's Best Public Undergraduate Colleges and Universities, Richard Moll included William & Mary as one of the original eight "Public Ivies". The university is among the original nine colonial colleges.

For 2019 Kiplinger ranked William & Mary 6th out of 174 best-value public colleges and universities in the U.S.[96]

According to the National Science Foundation, William & Mary is ranked 1st among public institutions for percentage of alumni who earn doctoral degrees in humanities fields.[97][98]

In the 2024-25 "America's Top Colleges" ranking by Forbes, W&M was ranked the 17th best public college and 55th out of the 500 best private and public colleges and universities in the U.S.[99] W&M ranked 3rd for race and class interaction in The Princeton Review's 2018 rankings.[citation needed] The college was ranked as the public college with the smartest students in the nation according to Business Insider's 2014 survey.[100]

The undergraduate business program was ranked 12th among undergraduate programs by the 2016 Bloomberg Businessweek survey.[101] Also in 2020, was W&M ranked 4th for "Colleges with the Happiest Students" by The Princeton Review[102] and 9th in a list of the public universities that "pay off the most", according to CNBC.[103] In 2022, Georgetown University's Center on Education and the Workforce ranked William & Mary's undergraduate business program #21 in value nationally.[104] In 2025, Poets & Quants ranked William & Mary's undergraduate business program #20 nationally.[105]

Publications

[edit]The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture publishes the William and Mary Quarterly, a scholarly journal focusing on colonial history, particularly in North America and the Atlantic World, from the Age of Discovery onward.

In addition to the Quarterly, W&M, by its mission to provide undergraduates with a thorough grounding in research, W&M also hosts several student journals. The Monitor, the undergraduate journal of International Studies, is published semi-annually. The Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History publishes an annual undergraduate history journal, the James Blair Historical Review.

Non-academic publications include The William & Mary Review – William & Mary's official literary magazine – Winged Nation – a student literary arts magazine, Acropolis – the art and art history magazine, The Flat Hat – the student newspaper, The Botetourt Squat – the student satirical newspaper, The Colonial Echo – William & Mary's yearbook, The DoG Street Journal – a daily online newspaper, and Rocket Magazine – William & Mary's fashion, art, and photography publication.[106][107][108][109][110]

Student life

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[111] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 59% | ||

| Asian | 10% | ||

| Hispanic | 9% | ||

| Black | 6% | ||

| Other[d] | 10% | ||

| Foreign national | 5% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[e] | 11% | ||

| Affluent[f] | 89% | ||

The college enjoys a temperate climate.[112] In addition to the college's extensive student recreation facilities (which include a large gym, a rock-climbing wall, and many exercise rooms) and programs (facilitating involvement in outdoor recreation, as well as club and intramural sports),[113] the largely wooded campus has its own lake and outdoor amphitheater. The Virginia Beach oceanfront is 60 miles (97 km) away, and Washington, D.C. is a 150-mile (240 km) drive to the north. Also, the beaches of the Delmarva Peninsula are just a few hours away via the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel.

The college's Alma Mater Productions (AMP) hosts concerts, comedians, and speakers on campus and in the 8,600-person capacity Kaplan Arena, as well as putting on many smaller activity-based events.[114] Students produce several publications on campus, including the official student newspaper The Flat Hat, arts and fashion magazine Rocket Magazine,[115] and the satirical newspaper The Botetourt Squat.[116] The school's television station, WMTV, produces content in the categories of cuisine, comedy, travel, and sports. Everyday Gourmet, the former flagship production of the station, was featured in USA Today in 2009.[117] WCWM, the college's student-run public radio station, transmits 24 hours a day on 90.9 FM locally and online [118] and features student-curated and created content; they also put on an annual concert, WCWM Fest, featuring local and touring musicians.[119]

The college also hosts several prominent student-run culture- and identity-based organizations. These include the Black Student Organization, Catholic Campus Ministry, Hillel (the college's official Jewish student group), Asian American Student Initiative, Latin American Student Union, Lambda Alliance and Rainbow Coalition, and the Middle Eastern Students Association, among many others.[120]

The college's International Relations Club (IRC) ranked eleventh of twenty-five participants in the 2020–2021 North American College Model U.N.[121]

Traditions

[edit]

William & Mary has several traditions, including the Yule Log Ceremony, at which the president dresses as Santa Claus and reads a rendition of "How the Grinch Stole Christmas", the Vice-President of Student Affairs reads "Twas the Night Before Finals", and The Gentlemen of the College sing the song "The Twelve Days of Christmas".[122] Christmas is a grand celebration at the college; decorated Christmas trees abound on campus. This popular tradition started when German immigrant Charles Minnigerode, a humanities professor at the college in 1842 who taught Latin and Greek, brought one of the first Christmas trees to America. Entering into the social life of post-colonial Virginia, Minnigerode introduced the German custom of decorating an evergreen tree at Christmas at the home of law professor St. George Tucker, thereby becoming another of many influences that prompted Americans to adopt the practice at about that time.[123]

Incoming first-year students participate in Opening Convocation, at which they pass through the entrance of the Wren Building and are officially welcomed as the newest members of the college. During orientation week, first-year students also have the opportunity to serenade the college president at his home with the Alma Mater song. The Senior Walk is similar in that graduating seniors walk through the Wren Building during their "departure" from college. On the last day of classes, Seniors are invited to ring the bell in the cupola of the Wren Building.

W&M also takes pride in its connections to its colonial past during Charter Day festivities. Charter Day is technically February 8, based on the date (from the Julian Calendar) that the Reverend James Blair, first president of the college, received the charter from the Court of William III and Mary II at Kensington Palace in 1693. Past Charter Day speakers have included former US President John Tyler, Henry Kissinger, Margaret Thatcher, and Robert Gates.[124]

Another underground tradition at W&M is known as the "Triathlon". As reported by The Flat Hat, the tradition - normally performed before graduation - involves completing three activities:[125] jumping the walls of the Governor's Palace in Colonial Williamsburg, streaking through the Sunken Garden, and finally swimming in the Crim Dell. The tradition has been referred to as an underground one and is not sanctioned by the college but is still widely practiced.[125]

Student Assembly

[edit]The Student Assembly is the student government organization serving undergraduates and graduates. It allocates a student organization budget and funds services, advocates for student rights, and is the formal student representation to the City of Williamsburg and William & Mary administration.[126] It consists of Executive, Legislative, and Judicial branches. The president and vice president are elected jointly by the student body to lead the Executive Branch, and each class elects one class president and four senators who serve in the Senate (the Legislative Branch). The five graduate schools appoint one to two senators. The Cabinet consists of 10 departments managed by secretaries and undersecretaries.[127]

Honor system

[edit]

William & Mary's honor system was established by alumnus Thomas Jefferson in 1779 and is widely believed to be the nation's first.[128] During the orientation week, every entering student recites the Honor Pledge in the Great Hall of the Wren Building pledging:

As a Member of the William & Mary community I pledge, on my Honor, not to lie, cheat, or steal in either my academic or personal life. I understand that such acts violate the Honor Code and undermine the community of trust of which we are all stewards.

The basis of W&M's Honor Pledge was written over 150 years ago by alum and law professor Henry St. George Tucker Sr.[129] While teaching law at the University of Virginia, Tucker proposed students attach a pledge to all exams confirming on their honor they did not receive any assistance.[130][131] Tucker's honor pledge was the early basis of the Honor System at the University of Virginia.[132] At W&M, the Honor System stands as one of the college's most important traditions; it remains student-administered through the Honor Council with the advice of the faculty and administration of the college. The college's Honor System is codified such that students found guilty of cheating, stealing, or lying are subject to sanctions ranging from a verbal warning to expulsion.[133]

W&M considers the observance of public laws of equal importance to the observance of its particular regulations. William & Mary's Board of Visitors delegates authority for discipline to its president. The President oversees a hierarchy of disciplinary authorities to enforce local laws as it pertains to William & Mary's interest as well as its internal regulatory system.[134]

Fraternities and sororities

[edit]

William & Mary has a long history of fraternities and sororities dating back to 1750 and the founding of the F.H.C. Society, the first collegiate fraternity established in what now is the United States. Phi Beta Kappa, the first "Greek-letter" fraternity, was founded at the college in 1776.

Today, various Greek-letter organizations play an important role in the college community and other social organizations such as theatre and club sports groups. Overall, about one-third of undergraduate students are active members of one or another of 16 national fraternities and 13 sororities.[135] William & Mary is also home to several unusual fraternal or similar organizations, including the Nu Kappa Epsilon music sorority[136] and its male counterpart, Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia; the Alpha Phi Omega co-ed service fraternity; gender-inclusive Phi Sigma Pi and other honor fraternities.

Secret societies

[edit]Several student secret societies exist at the college, including the F.H.C Society or Flat Hat Club, the Seven Society, the 13 Club, the Bishop James Madison Society, and the Wren Society.[137]

The Queens' Guard

[edit]

The Queens' Guard was established on February 8, 1961, as a special unit of the Army Reserve Officers' Training Corps and was affiliated with the Pershing Rifles. The Guard was described by former President Davis Young Paschall as "a unit organized, outfitted with special uniforms, and trained in appropriate drills and ceremonies as will represent the College of William & Mary in Virginia on such occasions and in such events as may be approved by the President." The uniform of the Guard loosely resembles that of the Scots Guards of the United Kingdom. The baldric is a pleated Stuart tartan in honor of Queen Mary II and Queen Anne.[138] Following a hazing citation in fall 2019 by the college's Community Values & Restorative Practices organization, the Queens' Guard was suspended until at least spring 2022.[139]

Music

[edit]

William & Mary has eleven collegiate a cappella groups: The Christopher Wren Singers (1987, co-ed); The Gentlemen of the College (1990, all-male); The Stairwells (1990, all-male); Intonations (1990, all-female); Reveille (1992, all-female); The Accidentals (1992, all-female); DoubleTake (1993, co-ed); The Cleftomaniacs (1999, co-ed); Passing Notes (2002, all-female); The Tribetones (2015, all-female);[140] and the Crim Dell Criers (2019, co-ed).[141][142] Sinfonicron Light Opera Company, founded in 1965, is William & Mary's student-run light opera company, producing musicals (traditionally those by Gilbert & Sullivan) in the early spring of each academic year.[143] Music societies at the college include local chapters of the music honor societies Delta Omicron (co-ed) and Phi Mu Alpha (all-male) as well as Nu Kappa Epsilon (all-female). Nu Kappa Epsilon, founded in 1994 at William & Mary, is "dedicated to promoting the growth and development of musical activities at the college as well as in the Williamsburg community".[144]

Large musical ensembles include a symphony orchestra, wind symphony, and four choral ensembles: The William & Mary Choir,[145] The Botetourt Chamber Singers,[146] The Barksdale Treble Chorus (formerly the William & Mary Women's Chorus), and Ebony Expressions Gospel Choir. The Botetourt Chamber Singers (1974, co-ed) are the student chamber choir.[147] There are several musical ensembles at the college, from Early Music Ensemble to Jazz.[148] Prior to 1996 the college had a marching band, which has since changed into the William & Mary Pep Band.[149]

William & Mary's radio station, WCWM, has been on the air since 1959.[150]

Comedy groups

[edit]William & Mary has multiple campus comedy groups. I.T. ("Improvisational Theatre") was founded in 1986 and is the oldest group on campus.[151] The sketch comedy ensemble 7th Grade Sketch Comedy has been in existence since 1997.[152] In 2012, Sandbox Improv was formed.[153] Dad Jeans Improv, established in 2016, specializes in long-form improvisation and technical elements.[154]

Athletics

[edit]

Formerly known as the "Indians", William & Mary's athletic teams are now known as the "Tribe". The college fields NCAA Division I teams for men and women in basketball, cross country, golf, gymnastics, soccer, swimming, tennis, and indoor and outdoor track and field. Also, there are women's field hockey, lacrosse, and volleyball squads, as well as men's baseball and football. In the 2004–05 season, the Tribe garnered five Colonial Athletic Association titles, leading the conference with over 80 titles. That same year, several teams competed in the NCAA Championships, with the football team appearing in the Division I-AA national semifinals. The men's cross country team finished 8th and 5th in Division I NCAA Men's Cross Country Championship in 2006 and 2009, respectively. The William & Mary men's basketball team is one of four original Division I schools that have never been to the NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament.[citation needed]

In May 2006, the NCAA ruled that the athletic logo, which includes two green and gold feathers, could create an environment offensive to the American Indian community. The college's appeal regarding using the institution's athletic logo to the NCAA Executive Committee was rejected. The "Tribe" nickname was found to be neither hostile nor abusive but rather communicates ennobling sentiments of commitment, shared idealism, community, and common cause.[155] The college stated it would phase out the use of the two feathers by the fall of 2007. However, they can still be seen prominently painted on streets throughout the campus.[156]

In 2018, athletic director Samantha Huge introduced a new brand kit for the department, officially retiring and de-emphasizing the script "Tribe" logo.[157]

The "Tribe 2025" plan, a comprehensive plan for the athletics department to raise national prominence, undergo significant facilities upgrades, and achieve higher levels of student involvement and spirit, was presented in 2019.[158] In 2020, William & Mary announced that due to financial concerns, they would be discontinuing seven varsity sports: men's and women's gymnastics, men's and women's swimming, men's indoor and outdoor track and field and volleyball.[159] This decision prompted a petition entitled "save the Tribe 7" which received significant support. On October 19, the university reinstated women's gymnastics, women's swimming, and volleyball after notice of an impending lawsuit on the grounds of Title IX violations.[160] President Rowe later announced that the decision to cancel the four men's programs would be put off until the 2021-2022 academic year.[160]

Notable people

[edit]Faculty

[edit]

Since the 17th century, many prominent academics have chosen to teach at William & Mary. Distinguished faculty include the first professor of law in the United States, George Wythe (who taught Henry Clay, John Marshall, and Thomas Jefferson, among others); William Small (Thomas Jefferson's cherished mentor); William and Thomas Dawson, who were also presidents of William & Mary. Also, the founder and first president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology – William Barton Rogers – taught chemistry at William & Mary (which was also Professor Barton's alma mater). Several members of the socially elite and politically influential Tucker family, including Nathaniel Beverley, St. George, and Henry St. George Tucker Sr. (who penned the original honor code pledge for the University of Virginia that remains in use there today), taught at William & Mary.

More recently, William & Mary recruited the constitutional scholar William Van Alstyne from Duke Law School. Lawrence Wilkerson, current Harriman Visiting Professor of Government and Public Policy, was chief of staff for Colin Powell. Susan Wise Bauer is an author and founder of Peace Hill Press, who teaches writing and American literature at the college. James Axtell, who teaches history, was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences as a Fellow in 2004. Iyabo Obasanjo, a previous senator of Nigeria and daughter of former President Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria, also serves as faculty in Kinesiology & Health Sciences.[161]

Professor Benjamin Bolger – the second-most credentialed person in modern history behind Michael Nicholson – taught at W&M.[162]

Alumni

[edit]Although a historically small college, the alumni of William & Mary include influential and historically significant people. Among its alumni are four of the first ten presidents of the United States,[163] four United States Supreme Court justices, dozens of U.S. senators, members of government, six Rhodes Scholars,[164] and three Marshall Scholars.[165]

-

3rd U.S. President, Thomas Jefferson (1762, attended)

-

10th U.S. President, John Tyler (class of 1807)

-

Commanding General of the U.S. Army, Winfield Scott (1805, attended)

-

9th U.S. Secretary of State, statesman, abolitionist, and Founder of the Whig Party, Henry Clay (class of 1797)

-

22nd United States Secretary of Defense and 24th Chancellor, Robert Gates (class of 1965)

-

7th Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, James Comey (class of 1982)

-

American singer-songwriter, Thao Nguyen (class of 2006)

-

American actress, Glenn Close (class of 1974)

-

American comedian, Jon Stewart (class of 1984)

-

Mayor of Minneapolis, Minnesota, Jacob Frey (class of 2004)

-

American comedian Michelle Wolf (class of 2007)

See also

[edit]- Williamsburg Bray School

- William & Mary scandal of 1951

- History of education in the Southern United States

Notes

[edit]- ^ The college gives its founding date as 1693, but it has not operated continuously since that time, having closed at two separate periods, 1861–1869 (during and following the Civil War) and later during 1882–1888; see Post-colonial history.

- ^ The full formal name of the college is "The College of William and Mary in Virginia".[7]

- ^ The independent Litchfield Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut, began offering formal legal education five years before William & Mary.

- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

[edit]- ^ "Search". the Internet Archive.

- ^ "About William & Mary". Archived from the original on July 15, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ As of December 1, 2024. Unaudited Consolidated Financial Report For The Year Ended June 30, 2024 (PDF) (Report). The College of William and Mary. December 1, 2024. Retrieved December 1, 2024.

- ^ "College Navigator - College of William & Mary". nces.ed.gov. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c "W&M at a Glance - William & Mary". nces.ed.gov. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "University Colors – University Guidelines". Archived from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ "Brand Guidelines: Editorial". Williamsburg, VA: College of William & Mary. Retrieved October 24, 2024.

- ^ Langley, Cortney (January 25, 2017). "The college that's a university". wm.edu. Williamsburg, VA: The College of William & Mary. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

The Code of Virginia takes a similar approach in defining W&M's legal name as 'The College of William & Mary', but uses 'The University' in subsequent references.

- ^ Morpurgo, J.E. (1976). Their Majesties Royall Colledge. Washington, D.C.: Hennage Creative Printers. p. 1. ISBN 0-916504-02-6.

- ^ "William & Mary". CARNEGIE CLASSIFICATION OF INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION. Retrieved February 14, 2025.

- ^ "William & Mary – History of the College". www.wm.edu. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees". wm.edu. College of William & Mary in Virginia. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "The Honor Code". William & Mary. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Coat of Arms". William and Mary Brand Guidelines. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "The Wren Building". William & Mary. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Earl Gregg Swem Library Special Collections". Swem.wm.edu. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Webster, Homer J. (1902) "Schools and Colleges in Colonial Times", The New England Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly, v. XXVII, p. 374, Google Books entry

- ^ "The Silence of the Graves by Terry L. Meyers". Archived from the original on July 16, 2002.

- ^ Blondel-Libardi, Catherine R. (2007). "Rediscovering the Litchfield Law School Notebooks". Connecticut History Review. 46 (1): 70–82. doi:10.2307/44369759. ISSN 0884-7177. JSTOR 44369759. S2CID 254480254.

- ^ "Virginia Vignettes » What Was the Brafferton School?". Virginiavignettes.org. August 2007. Archived from the original on November 11, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Shhh! The Secret Side to the College's Lesser Known Societies". The DoG Street Journal. Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Peeking Into Closed Societies – The Flat Hat". Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ Brophy, Alfred L. (2016). University, Court, and Slave: Proslavery Thought in Southern Courts and Colleges and the Coming of Civil War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-062593-1.

- ^ Barnes, II, F. James. "William & Mary Alumni > History". Alumni.wm.edu. Archived from the original on September 24, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Gordon, John Brown (1903). Reminiscences of the Civil War. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 422.

- ^ "1850–1899 | Historical Facts". Historical Chronology of William and Mary. Wm.edu. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Earl Gregg Swem Library Special Collections". Swem.wm.edu. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Freehling, Alison (October 2, 1996). "Light of Learning to Shine in Teacher's Memory". Daily Press. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- ^ Women at UVa: Graduate and Professional Schools Archived February 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. .lib.virginia.edu. Retrieved on August 9, 2013.

- ^ Gonzales, Donald J. (1991). The Rockefellers at Williamsburg: Backstory with the Founders, Restorers and World-Renowned Guests. McLean, VA: EPM Publications. pp. 25–26. ISBN 0-939009-58-7.

- ^ Greenspan, Anders (2009) [2002]. Creating Colonial Williamsburg: The Restoration of Virginia's Eighteenth-Century Capital (2nd ed.). University of North Carolina Press. pp. 18, 51–52. ISBN 978-0-8078-5987-2.

- ^ Wilson, Richard Guy, ed. (2002). Buildings of Virginia: Tidewater and Piedmont. Buildings of the United States. Oxford University Press, Society of Architectural Historians. pp. 361, 374–376. ISBN 0-19-515206-9.

- ^ Sherman, Richard B. (1993). "Part V: Chapter 1". The College of William & Mary: A History: Volume II. Williamsburg, VA: King and Queen Press, Society of the Alumni, The College of William and Mary in Virginia. p. 558.

- ^ "Roosevelt's Address at William and Mary". The New York Times. "Roosevelt's Address at William and Mary". The New York Times. October 21, 1934. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2009.. (October 21, 1934). Retrieved on August 9, 2013.

- ^ Education: Jefferson's Heirs Archived August 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Time, February 26, 1945

- ^ "Marilyn Kaemmerle". wm.edu. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012.

- ^ "A Michigan Woman, Race Relations, and Virginia 1945". William & Mary Libraries. March 3, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ "About the Memorial". College of William & Mary. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Wallenstein, Peter. "Desegregation in Higher Education in Virginia". Archived from the original on July 10, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ^ Godson; et al. (1993). The College of William and Mary: A History. King and Queen Press. ISBN 0-9615670-4-X.

- ^ "Ash Lawn-Highland, Home of James Monroe". Ashlawnhighland.org. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Special Collections Research Center (2013). "Jefferson Hall Fire: 30th Anniversary". William & Mary Libraries. Archived from the original on October 25, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Whitson, Brian (July 25, 2012). "W&M and EVMS to explore School of Medicine". The College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ Reveley, Taylor (July 25, 2012). "President's message on W&M and EVMS". The College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ Whitson, Brian (January 16, 2013). "W&M report recommends pilot partnership with EVMS". The College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ Langley, Cortney (March 13, 2015). "Great Britain's royalty is at home at William & Mary". The College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- ^ "Queen's Platinum Jubilee in Williamsburg, Virginia USA". Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ ""America's most beautiful college campuses", Travel+Leisure (September 2011)". Travel + Leisure. Archived from the original on December 2, 2014. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- ^ "Wren Building, College of William and Mary". National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ Larson, Chiles T.A. (Fall 2005). "Did Wren Design the Building and William and Mary Bearing His Name?" (PDF). William & Mary. 71 (1). W&M Alumni Association: 59. Archived from the original on April 13, 2015. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ Smith, Sarah (April 18, 2016). "Alumni group presents three faculty awards". The Flat Hat. Williamsburg, VA. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ Coviello, Brianna (October 17, 2013). "Brafferton's running boy". The Flat Hat. Williamsburg, VA. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ Kale, Wilford (August 5, 2022). "So far, so good in construction of new hall at W&M". Daily Press. Williamsburg, VA. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Byrne, Alexandra (April 23, 2021). "College renames Morton, Taliaferro, Tyler following months of pressure from students, faculty". The Flat Hat. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ "Facts about Lake Matoaka". College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ Zagursky, Erin; Whitson, Brian (September 25, 2020). "W&M board approves principles for naming, renaming campus spaces". College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on March 12, 2021. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Faculty Handbook" (PDF). 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ "Members of the Board". Board of Visitors, The College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ "Duties and History, Chancellor". College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ Ukman, Jason (September 6, 2011). "Gates takes chancellor's post at William and Mary". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- ^ "W. Taylor Reveley, President". College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ "William & Mary announces Katherine Rowe as 28th President". William & Mary News Archive. February 20, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ "Greenwich Hospital School: A Brief History of The Royal Hospital School". Mariners. March 5, 2003. Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ a b "Carnegie Classifications: College of William and Mary". The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ William & Mary – St Andrews William & Mary Joint Degree Programme Archived April 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Wm.edu. Retrieved on August 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "Common Data Set 2018–2019, Part B". Office of Institutional Research, College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "SACS at William & Mary". College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ "Departments and Schools". www.wm.edu. College of William and Mary in Virginia. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Schools and Departments. William & Mary.

- ^ Batten School of Coastal & Marine Sciences. Virginia Institute of Marine Science. College of William & Mary.

- ^ "Topic Galleries – dailypress.com". Dailypress.com. September 26, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Common Data Set". William & Mary Institutional Data. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20250214200455/https://www.wm.edu/offices/it/services/ir/university_data/cds/cds-2024-2025_b1.pdf

- ^ "College of William and Mary – Best College – Education – US News". Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ https://www.wm.edu/offices/it/services/ir/university_data/cds/cds-2024-2025_c.pdf

- ^ "Tuition & Fees". William & Mary. Retrieved February 14, 2025.

- ^ "Common Data Set 2015–2016, Part H". Office of Institutional Research, College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ Burd, Stephen (April 18, 2017). "New Data Reveals, For First Time, Each Colleges' Share of Rich Kids". New America. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ Burd, Stephen (March 2016). "Undermining Pell: Volume III" (PDF). New America. p. 23. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ "Financial Aid". College of William and Mary. Archived from the original on December 22, 2020. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds. June 4, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. September 27, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. June 24, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ a b "College of William and Mary Graduate School Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ "W&M's colonial history grad program ranked #1 by U.S. News". William & Mary. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ "2021 Best Undergraduate Teaching Programs at National Universities | US News Rankings". May 29, 2021. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ a b "William & Mary Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ "US News and World Report-- William & Mary Global Rankings".

- ^ "William & Mary". Forbes. Retrieved February 14, 2025.

- ^ "Rankings | Colleges with the highest SAT scores - Average SAT score rankings | Control | Public". www.collegeraptor.com. Retrieved February 12, 2025.

- ^ "Rankings | Colleges with the best 4-year graduation rate - Most graduates in 4 years | Control | Public". www.collegeraptor.com. Retrieved February 12, 2025.

- ^ "Kiplinger's College Finder". Kiplinger's Personal Finance. July 2019. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED619081.pdf

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20250202190702/https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED619081.pdf

- ^ "William & Mary". Forbes. Retrieved February 19, 2025.

- ^ Education (March 24, 2014). "20 Public Colleges With Smartest Students". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 21, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- ^ "Best Undergraduate Business Schools 2016". Businessweek.com. April 19, 2016. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ^ "Colleges with the Happiest Students". The Princeton Review. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ "The top 50 U.S. Colleges that pay off the most in 2020". CNBC. July 28, 2020.

- ^ "The Most Popular Degree Pays Off: Ranking the Economic Value of 5,500 Business Programs at More Than 1,700 Colleges". CEW Georgetown. Retrieved February 12, 2025.

- ^ Bleizeffer, Kristy (March 17, 2025). "Poets&Quants' Best Undergraduate Business Schools Of 2025". Poets&Quants for Undergrads. Retrieved March 17, 2025.

- ^ "About". Dog Street Journal. Retrieved February 2, 2025.

- ^ "rocketmagazine Publisher Publications". Issuu. Retrieved February 2, 2025.

- ^ "About The Flat Hat". Flat Hat News. January 31, 2025. Retrieved February 2, 2025.

- ^ "Colonial Echo". W&M Libraries Digital Collections. Archived from the original on September 17, 2024. Retrieved February 2, 2025.

- ^ "About". THE BOTETOURT SQUAT. Retrieved February 2, 2025.

- ^ "College Scorecard: William & Mary". United States Department of Education. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "KeckWeather". Wm.edu. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "William & Mary Recreation". Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "The Flat Hat". Flat Hat News. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- ^ "Rocket Magazine". Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "The Botetourt Squat". Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Harpaz, Beth J. (July 24, 2009). "Ramen noodles no more? College students go gourmet". USA Today. Education. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ "WCWM, 90.9 FM, Richmond, VA". Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "WCWM 90.9 FM". Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Organizations - TribeLink". Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Zoey Fisher (May 26, 2021). "2020-2021 North American College Model U.N. Final Rankings (World Division)". Best Delegate. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ "Holiday Traditions Fill The Season In Williamsburg". Chattanoogan.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Minnigerode, Charles (1814–1894) Archived August 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved on August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Charter Day Speakers". William & Mary Special Collections Research Center. January 20, 2015. Archived from the original on October 1, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Hat, The Flat (August 22, 2008). "The College's very own triathlon tradition | Flat Hat News". Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ "About". Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ "Branches". Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ Olsen, Patricia R. (January 6, 2008). "And Out of the Corner of My Eye..." The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Tucker, Henry St. George, (1780–1848)". Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ^ Barefoot, Coy (Spring 2008). "The Evolution of Honor: Enduring Principle, Changing Times". The University of Virginia Magazine. 97 (1). Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Alumni Assn.: 22–27. Archived from the original on March 29, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

- ^ Smith, C. Alphonso (November 29, 1936). "'I Certify On My Honor--' The Real Story of How the Famed 'Honor System' at University of Virginia Functions and What Matriculating Students Should Know About It". Richmond Times Dispatch. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ^ Bruce, Philip Alexander (1921). History of the University of Virginia: The Lengthened Shadow of One Man. Vol. III. New York: Macmillan. pp. 68–69. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Judicial Affairs |". Wm.edu. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Student Code of Conduct". Wm.edu. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ "Chapters". Wm.edu. February 4, 2013. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ^ "What Exactly is Nu Kappa Epsilon?". Retrieved February 12, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Peeking into closed societies". Flat Hat News. April 8, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "The Queens' Guard Homepage and Pershing Rifles Co. W-4". College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- ^ Community Values & Restorative Practices. "Student Organization Conduct History". Williamsburg, VA: College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ "W&M a cappella council homepage". Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- ^ "Life@W&M on Instagram". College of William and Mary Official Instagram account. December 10, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

Today is a very exciting day! Last spring, a friend and I decided to start a new acapella group. The Crim Dell Criers is a noncompetitive "informal" coed rockapella group. ... It took all fall but finally, as of November, we are an official club on campus!

- ^ "Crim Dell Criers". College of William and Mary. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ Cleverly, Casey (January 25, 2007). "Sinfonicron Presents The Mikado" Archived March 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. The DoG Street Journal

- ^ Thompson, Camille (2005). College of William and Mary Archived May 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, p.159. College Prowler Inc. ISBN 1-59658-031-3

- ^ "William & Mary - W&M Choir". William & Mary. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ "William & Mary - Botetourt Chamber Singers". William & Mary. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ "Botetourt Chamber Singers". Williamsburg, VA: College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on February 2, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ "Classical & Jazz Ensembles". College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "The William & Mary Pep Band". William & Mary Pep Band. Archived from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "WCWM Fest". WCWM Fest. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ "Improvisational Theatre at the College of William & Mary". Archived from the original on September 15, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "7th Grade Sketch Comedy - History". sites.google.com. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ "Sandbox Improv: New group on campus adds to comedy community". Flat Hat News. January 17, 2013. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- ^ "Comedy at the College: Various college comedy groups hold the VCCIs". Flat Hat News. January 17, 2013. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- ^ "'Tribe' refers to community Nichol states in a report sent to the NCAA | University Relations". Wm.edu. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "William and Mary to change athletic logo before Fall 2007 | University Relations". Wm.edu. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ "William & Mary Athletics Reveals Revitalized Brand and Logo". William & Mary Athletics. July 25, 2018. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ William & Mary Athletics sets ambitious goals in strategic plan 'Tribe 2025' https://www.wm.edu/news/stories/2019/william-mary-athletics-sets-ambitious-goals-in-strategic-plan-tribe-2025.php Archived January 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Johnson, Dave (September 3, 2020). "Amid financial concerns, W&M to discontinue seven sports following the 2020-2021 academic year".

- ^ a b "New life for the "Tribe 7"". November 16, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ "Iyabo Obasanjo". wm.edu. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2021.

- ^ "Twenty-seven degrees and counting: Kalamazoo man enjoys the 'freedom' of intellectual pursuits". MLive.com. January 19, 2009. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ "Incredible Alumni". William & Mary. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ "Senior named Rhodes Scholar, sixth in College's history". Williamsburg, VA: The College of William & Mary in Virginia. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- ^ "Student awarded prestigious Marshall Scholarship: Third in College's history". William & Mary. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Allen, Jody L. "Thomas Dew and the rise of proslavery ideology at William & Mary." Slavery & Abolition 39.2 (2018): 267-279.

- Meyers, Terry L. "Thinking about Slavery at the College of William and Mary." William and Mary Bill of Rights Journal 21 (2012): 1215+.

- Thomson, Robert Polk. "The reform of the College of William and Mary, 1763-1780." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 115.3 (1971): 187-213.

- Wenger, Mark R. "Thomas Jefferson, the College of William and Mary, and the University of Virginia." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 103.3 (1995): 339-374. online

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Drone, Eaton S. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- Transcript of the Royal Charter

Logo since 2011 | |

299 Queen Street West, the former headquarters of CHUM Limited, serves as the headquarters of Bell Media, in 2022. | |

| Formerly |

|

|---|---|

| Company type | Subsidiary |

| Industry | Mass media |

| Founded |

|

| Headquarters | 299 Queen Street West, , Canada |

Area served | Canada |

Key people |

|

Number of employees | 5,000+ |

| Parent | BCE Inc. |

| Divisions | |

| Subsidiaries | CTV Specialty Television (joint venture with ESPN Inc.) |

| Website | www |

| Footnotes / references [1][2] | |

Bell Media Inc. (French: Bell Média inc.)[1] is a Canadian media conglomerate that is the mass media subsidiary of BCE Inc. (also known as Bell Canada Enterprises, the owner of telecommunications company Bell Canada). Its operations include national television broadcasting and production (including the CTV and CTV 2 television networks), radio broadcasting (through iHeartRadio Canada), digital media (including Crave) and Internet properties (including the now-defunct Sympatico portal).

Bell Media is the successor-in-interest to Baton Broadcasting (later CTV Inc.), one of Canada's first private-sector television broadcasters. Although the company was founded in 1960 as Telegram Corporation, the current enterprise traces its origins to the establishment of Bell Globemedia Inc. in 2001 by BCE and the Thomson family, combining CTV Inc. (which BCE had acquired in 2000) and the operations of the Thomson family's newspaper, The Globe and Mail. BCE sold the majority of its interest in 2006 (after which the company was renamed CTVglobemedia Inc. in 2007), but in 2011, BCE acquired the entire company (excluding The Globe and Mail) and changed the name to Bell Media Inc.

Origins

[edit]Baton Broadcasting

[edit]For all practical purposes, Bell Media is the successor to Baton Broadcasting Incorporated (/ˈbeɪtɒn/ BAY-ton), which by the late 1990s had become one of Canada's largest broadcasters.

Formed in 1960 as Baton Aldred Rogers Broadcasting Ltd., the company was originally created to establish Toronto's first private television station, CFTO-TV. The name of this company derived from its initial investors, including the Bassett and Eaton families (Baton), and Aldred-Rogers Broadcasting (owned by broadcaster Joel Aldred[3] and Ted Rogers); Foster Hewitt was also an initial investor, but in a much smaller role.[4] Aldred sold his shares in 1961, followed by Rogers by 1970, thereby relieving their names from the company title. With the Bassett and Eaton families firmly in control, the company went public in the early 1970s.

CFTO was one of the charter affiliates of CTV when that network formed in 1961, becoming the network's flagship. In 1966, Baton became a part-owner in the network when it was reorganized as a station-owned cooperative. The Board of Broadcast Governors was initially skeptical about the proposal to turn CTV into a cooperative. Since CFTO was by far the largest and richest station in the network, the BBG feared Baton would take advantage of this to dominate the network. However, it approved the deal after Baton and the other owners included a provision in the cooperative's bylaws stipulating that the eight station owners would each have a single vote regardless of audience share. Additionally, if one owner ever bought another station, the acquired station's shares would be redistributed among the remaining owners so that each owner would still have one vote out of eight.

In 1972, Baton began purchasing other CTV affiliates, starting with CFQC-TV in Saskatoon. This did not, however, give Baton a substantially higher investment in CTV, since its shares were redistributed among the other owners. As a result, Baton still had only one vote out of eight.

In 1987, Baton began a concerted effort to take over CTV. It started this drive with a further expansion into Saskatchewan, purchasing CKCK-TV in Regina, Yorkton twinstick CKOS-TV/CICC-TV, and CBC affiliate CKBI-TV Prince Albert. A twinstick CTV affiliate was soon launched in Prince Albert, CIPA-TV.

In the late 1980s, Baton applied for a high-power station in Ottawa on channel 60. The licence was approved by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), appealed to federal cabinet by rival broadcasters, and ultimately sent back to the CRTC for review.[5] However the license was surrendered when Baton was instead able to acquire the local CTV affiliate, CJOH-TV, from Allan Slaight's Standard Broadcasting.

In 1990, Baton purchased the MCTV system of twinstick operations in Pembroke, North Bay, Sudbury, Timmins, and the Huron Broadcasting twinstick in Sault Ste. Marie. In 1993, Baton purchased CFPL-TV in London, CKNX-TV in Wingham and received a license for a new independent station, CHWI-TV, in Windsor.